Although not long ago, the central bank announced that the one-year and five-year loan prime rates (LPR) for June would remain unchanged at 3.45% and 3.95%, respectively, which means no interest rate cuts for four consecutive months.

However, against the backdrop of the real estate market's inventory reduction, in the future, not only might there be no interest rate cuts, but it's even possible that rates could be reduced to below 1% or even reach zero interest rates.

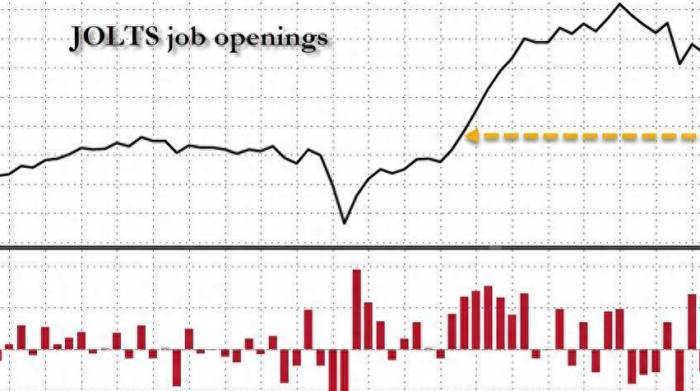

Let's first look at some data sets:

Since the "5.17" new policy, various regions have already lowered the down payment for purchasing a home to 15%, and the mortgage interest rates have also been historically reduced to around 3%. However, in May, the housing prices in first-tier cities decreased by 0.7% month-on-month, the sales area of new homes decreased by 23.6% year-on-year, and the unsold commercial housing area increased by 24.6% year-on-year.

This means that the central bank's major move only maintained its effect for about a week. Although the transaction volume in some cities has rebounded, the national real estate market still hasn't been able to change its downward trend.

The policy has done its best, but the effect of reducing inventory is not ideal.

Additionally, in May, M1 decreased by 4.2% year-on-year. Experts have come forward to advise everyone to be rational, stating that the slowdown in the growth of the total money supply does not mean a reduction in the financial support for the real economy. The growth rate of M1 may be underestimated, and the current statistical methods cannot fully reflect the current economic activities.

Regarding "experts," especially "economic experts," everyone understands what's going on.

The "moving" of corporate demand deposits is mainly due to the continuous reduction of our loan interest rates, which has led to the net interest margin of banks being reduced to 1.54%, and the deposit interest rates also have to be adjusted downward accordingly.In a nutshell, demand deposits are not cost-effective.

For instance, the three-year interest rate of rural and township banks, which used to offer higher returns, has dropped to 2.5%. Large banks have ceased offering long-term, large-amount deposits with limits. The 30-year ultra-long-term special government bonds, once a hot item, have seen their yields fall below 2.5%.

These two sets of data actually indicate one thing: that funds are not circulating idly within the system but are not circulating at all. Essentially, we are facing a scarcity of assets and a panic over asset devaluation.

As banks lower their deposit interest rates, people's expectations for future investment returns are also diminishing. It's as if a series of moves have been made with no effective damage, and instead of a rebound in consumption, people are holding onto their money tighter. Many have switched from demand deposits to long-term ones, and consumption has become more rational.

However, the current situation is that to invigorate the economy, we need to reduce the inventory in the real estate market. The simplest and most effective way to do this is to lower mortgage interest rates, which inevitably leads to a decrease in bank deposit interest rates as well.

In a challenging environment, the ability of individuals and families to withstand risks also declines. Investments are prone to pitfalls, and not starting a business could mean a high probability of unemployment in middle age. There's always a pitfall, big or small, waiting for you in life.

Let's get back to the main topic.

The central bank's reluctance to cut interest rates is probably due to monitoring the yuan exchange rate. The Federal Reserve has already postponed interest rate cuts until 2025. Maintaining the status quo is more conducive to trade surpluses and attracting foreign investment, and it enhances the appeal of yuan assets.

In other words, if the Federal Reserve cuts interest rates, we will most likely follow suit.

In fact, some countries have already reached their limits. In early June, the European Central Bank announced a rate cut, and Canada and Mexico in the North American Free Trade Area have also lowered their benchmark interest rates.The global economy is entering a cycle of interest rate cuts, with only the small neighbor to the east going against the trend. Having just lifted its negative interest rate policy in March, the bond market is now anticipating further rate hikes.

The reason is not complicated: the Japanese yen has hit a new low not seen in over 30 years. If the Japanese government does not intervene, the assets of the island nation will continue to shrink, and the harm of currency devaluation will ultimately be borne by the entire population.

So the future is not a question of whether to cut rates or not, but how much to cut. If interest rates are reduced to 1% or even zero, what will you, the viewer, do to cope?

Of course, when it comes to the survival strategies in the era of zero interest rates, the small neighbor to the east has the most to say.

As everyone knows, after the bubble burst in Japan in the 1990s, the stock market lost one-third of its value within a year, and real estate prices plummeted even more. National housing prices dropped by 70% from their peak during the bubble, and Tokyo's housing prices plummeted by 90%. Over a decade, more than 180 banks went bankrupt one after another, with the economic loss caused by the bubble burst estimated at 208 trillion yen.

To stimulate the economy, the Bank of Japan implemented a zero interest rate policy as early as 1999, and later, in 2016, it innovatively introduced a negative interest rate policy when it was found to have little effect.

This means that not only do you not receive any interest on money deposited in the bank, but you also have to pay the bank a storage fee, not to mention the asset loss brought about by currency devaluation.

Logically, such a counterintuitive approach would inevitably lead to passionate consumption in society, but what did the Japanese do?

They still chose to keep their money in the bank because someone calculated that if the inflation rate of that year was lower than the short-term bank deposit interest rate, the actual return on deposits would still be a sure gain.

Let's talk about the data: in 2020, the Japanese government's expected inflation rate was -0.7%, while the short-term bank deposit interest rate was -0.1%. By offsetting these two, the actual return on deposits was still 0.6%.So, a magical phenomenon has emerged: even with negative interest rate policies, Japanese citizens still dutifully deposit their money in banks or buy government bonds with yields of less than 1%.

In 2022, the average financial assets of Japanese households were 19 million yen, roughly equivalent to over 900,000 RMB in our currency, with only 15.5% of assets in stocks and 54% in bank deposits that offer virtually no interest.

When the economic environment is poor and investment channels are limited, never underestimate the confidence and perseverance of the common people in careful financial planning; the interest rate differential is their most adept and stable financial management tool.

Of course, the era of negative interest rates is not without opportunities. Japanese housewives have adeptly seized this systemic glitch by borrowing yen at low interest rates, then exchanging them for foreign currencies with higher interest rates, and investing in high-yield foreign bonds or foreign exchange deposits to earn the interest rate spread. The only risk lies in the appreciation of the yen.

This strategy not only made the housewives financially prosperous but also unexpectedly changed the global financial landscape. Later, this economic phenomenon was termed "Mrs. Watanabe," which essentially refers to the ordinary Japanese housewives.

Of course, with no regulations in Japan, "Mrs. Watanabe" can thrive in foreign exchange trading, whereas we do not have such conditions, so we might see a surge of housewives speculating heavily in gold.

The forms may differ, but the outcomes are similar, both reflecting the diligence and intelligence of the general public in the era of low interest rates.

The final question for everyone: if bank interest rates drop below 1%, while existing mortgage rates remain at 3%-4%, and in an environment without investment channels offering returns above 3%, would people vote with their feet and prepay their 20-year mortgages?

Leave a Comment